AMAZON DESTRUCTION

Deforestation data is annual on this page. Monthly updates are here.

Since 1978 over 750,000 square kilometers (289,000 square miles) of Amazon rainforest

have been destroyed across Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Bolivia, Venezuela,

Suriname, Guyana, and French Guiana. Why is Earth's largest rainforest being destroyed?

For most of human history, deforestation in the

Amazon was primarily the product of subsistence farmers who cut down

trees to produce crops for their families and local consumption. But in

the later part of the 20th century, that began to change, with an

increasing proportion of deforestation driven by industrial activities

and large-scale agriculture. By the 2000s more than three-quarters of

forest clearing in the Amazon was for cattle-ranching.

The result of this shift is forests in the Amazon

were cleared faster than ever before in the late 1970s through the mid

2000s. Vast areas of rainforest were felled for cattle pasture and soy

farms, drowned for dams, dug up for minerals, and bulldozed for towns

and colonization projects. At the same time, the proliferation of roads

opened previously inaccessible forests to settlement by poor farmers,

illegal logging, and land speculators.

But that trend began to reverse in Brazil in 2004.

Since then, annual forest loss in the country that contains nearly

two-thirds of the Amazon's forest cover has declined by roughly eighty

percent. The drop has been fueled by a number of factors, including

increased law enforcement, satellite monitoring, pressure from

environmentalists, private and public sector initiatives, new protected

areas, and macroeconomic trends. Nonetheless the trend in Brazil is not

mirrored in other Amazon countries, some of which have experienced

rising deforestation since 2000.

However Brazil's success in curbing deforestation has

stalled since 2012. And in July 2019, deforestation soared to levels

not seen since the mid-2000s. [Amazon deforestation rises to 11 year high in Brazil (Nov 18, 2019)]

Deforestation trends in Amazon countries

Forest loss trends between Amazon countries are

highly variable. The following charts are based data from Matt Hansen

and colleagues, as presented in Global Forest Watch, using a "loose"

definition of the Amazon that extends beyond the Amazon river basin.

This includes the Guianas, all of Amazonas state in Venezuela, and all

of the states of Maranhão and Mato Grosso in Brazil. Forest is defined

as areas having more than 50 percent tree cover.

Please note: Amazon deforestation data is updated monthly here.

Brazil

Brazil [news]

holds about one-third of the world's remaining rainforests, including

more than 60 percent of the Amazon rainforest. Deforestation in the

Brazilian Amazon declined sharply in the mid-2000s due to government

interventions, macroeconomic factors, and efforts by civil society.

However in recent years, that decline has stalled, with deforestation

beginning to rise again.

The history of dramatic decline in the Brazilian Amazon's deforestation rate is detailed in our environmental profile on the country. For updates on deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, check our Brazil deforestation news feed.

Peru

Peru's [news]

rate of forest loss has been trending upward over the past decade.

Reasons for the rise include the development and completion of the

Transoceanic highway, which connects Pacific ports to the heart of the

Amazon; a surge in gold mining in Madre de Dios and other regions along

the eastern slope of the Andes; and increased logging and hydrocarbon

extraction.

Colombia

The rate of forest loss in the Colombian Amazon [news] has been roughly flat since 2000.

Bolivia

Bolivia's [news]

deforestation spiked in 2008 and again in 2010. Overall the country's

rate of loss has been increasing at the second highest rate in the

Amazon.

Ecuador

Ecuador's [news]

rate of forest loss in the Amazon increased between 2001 and 2012. One

of the top concern for environmentalists is the government's decision to

open Yasuni National Park for oil drilling.

Venezuela

Only a part of Amazonas state in Venezuela [news]

is considered part of the Amazon rainforest, but for the purpose of

this estimate, the entire state is used. Most of Venezuela's rainforest

found in areas that are part of the Orinoco river basin. Forest loss in

the Venezuelan Amazon has been mostly flat since 2000.

The Guianas

While Suriname [news], Guyana [news], and French Guiana [news]

aren't part of the Amazon River basin, their forests are often lumped

in as part of the Amazon rainforest. Forest loss in the three countries

has sharply increased in recent years.

Drivers of deforestation in the Amazon

Several trends are contributing to industrial conversion in the Amazon rainforest:

- Increased government incentives in the form of loans and infrastructure spending, including roads and dams;

- Scaled-up private sector finance due to growing interest in "emerging markets" and rising domestic wealth;

- Surging demand for commodities like beef, soy, sugar, and palm oil

Direct drivers of deforestation in Amazon countries

Cattle ranching

Cattle ranching is the leading cause of deforestation

in the Amazon rainforest. In Brazil, this has been the case since at

least the 1970s: government figures attributed 38 percent of

deforestation from 1966-1975 to large-scale cattle ranching. Today the

figure in Brazil is closer to 70 percent. Most of the beef is destined

for urban markets, whereas leather and other cattle products are

primarily for export markets.

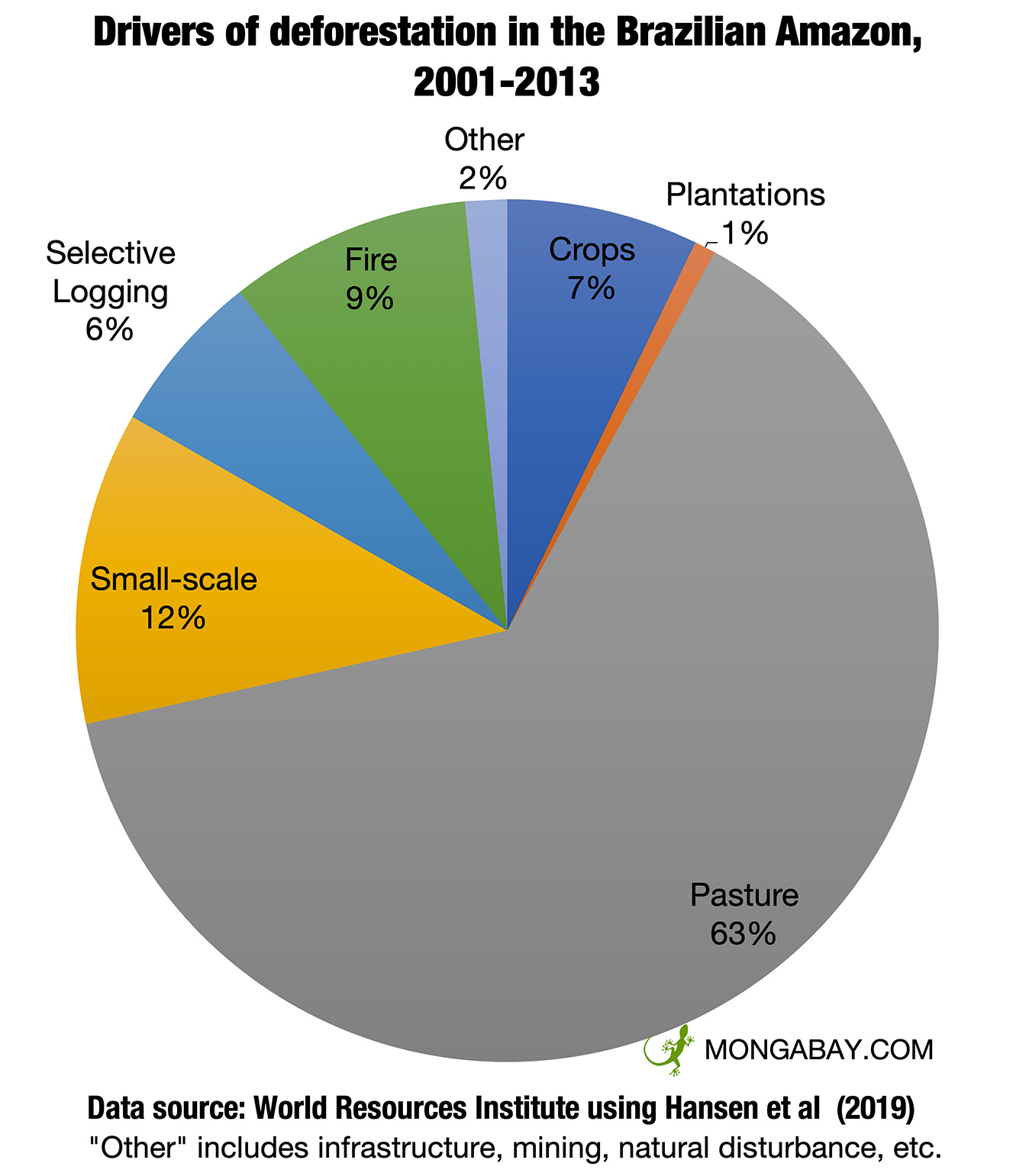

| Causes of deforestation in the Amazon, 2001-2013 | Share of direct deforestation |

|---|---|

| Cattle ranching | 63% |

| Small-scale agriculture Includes both subsistence and commercial | 12% |

| Fires Sub-canopy fires often result in degradation, not deforestation | 9% |

| Agriculture Large-scale industrial agriculture like soy and plantations | 8% |

| Logging Selective logging commonly results in degradation, not deforestation | 6% |

| Other Mining, urbanization, road construction, dams, etc. | 2% |

But production of beef, leather and other cattle

products isn't the only reason for converting rainforest into artificial

grasslands. In a region where land prices are appreciating quickly,

cattle ranching is used as a vehicle for land speculation, much of which

is illegal. Forestland has little value—but cleared pastureland can be

used to produce cattle or sold to large-scale farmers, including soy

planters.

However the situation — at least in the Brazilian

Amazon — may be starting to change. Since 2009 major cattle buyers and

the Brazilian government — pushed by environmental campaigners — have

cracked down on deforestation for cattle production. State-run banks are

now mandating landowners register their properties for environmental

compliance in order to gain access to low-interest loans. Meanwhile

major slaughterhouses have pledged stricter controls on their cattle

sourcing to ensure they aren't driving deforestation or the use of slave

labor on ranches.

Such trends have yet to emerge in Peru, Bolivia, and

Colombia, where cattle ranching remains a major driver of Amazon forest

loss.

Colonization and subsequent subsistence agriculture

Historically, subsistence agriculture has been an

important cause of deforestation in the Amazon. Small-scale agriculture

has often been facilitated by government colonization programs aiming to

alleviate urban population pressure by redistributing or granting rural

land to the poor. In some cases these programs have failed to meet

their development goals while simultaneously unleashing an environmental

Armageddon.

For example in the 1970s, Brazil's military

dictatorship expanded its ambitious colonization program centered around

the construction of the 2,000-mile Trans-Amazonian Highway, which would

bisect the Amazon, opening rainforest lands to (1) settlement by poor

farmers from the crowded, drought-plagued north and (2) enabling the

exploitation of timber and mineral resources. Under the program,

colonists would be granted a 250-acre lot, six-months' salary, and easy

access to agricultural loans in exchange for settling along the highway

and converting the surrounding rainforest into agricultural land. The

plan would grow to cost Brazil US$65,000 (1980 dollars) to settle each

family.

The project was plagued from the start. The

sediments of the Amazon Basin rendered the highway unstable and subject

to inundation during heavy rains, blocking traffic and leaving crops to

rot. Harvest yields for poor farmers were dismal due to poor training

and inadequate soils, which were quickly exhausted necessitating more

forest clearing.. Logging was difficult due to the low density of

commercially exploitable trees. Rampant erosion, up to 40 tons of soil

per acre (100 tons/ha) occurred after clearing. Many colonists,

unfamiliar with banking and lured by easy credit, went deep into debt.

Adding to the debacle was the environmental cost of

the project. After the construction of the Trans-Amazonian Highway,

Brazilian deforestation accelerated to levels never before seen.

Commercial agriculture

After the commercialization of a new variety of

soybean developed by Brazilian scientists to flourish in rainforest

climate, soy emerged as one of the most important contributors to

deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon from the 1990s through the

mid-2000s.

Soy was both a direct and indirect deforestation.

While forest was converted directly for soy fields, the crop's impact on

rainforests was much larger, providing an impetus for new highways,

driving up land prices and thereby encouraging land speculation, and

encouraging ranchers and small farmers to move deeper into rainforest

areas.

But the situation in Brazil has changed significantly

since 2006, when a high profile campaign by Greenpeace forced Brazil's

largest soy producers to commit to avoiding deforestation for new

production. However deforestation for soy is still widespread in Bolivia

and Paraguay.

Meanwhile other forms of commercial agriculture,

including rice, corn, and sugar cane, also contribute to deforestation

in the Amazon, both directly through forest conversion and indirectly by

driving up land values.

Logging

In theory, logging in the Amazon is controlled by

strict licensing which allows timber to be harvested only in designated

areas, but in practice, illegal logging remains widespread in Brazil and

Peru.

Logging in the Amazon is closely linked with road

building. Studies by the Environmental Defense Fund show that areas that

have been selectively logged

are eight times more likely to be settled and cleared by shifting

cultivators than untouched rainforests because of access granted by

logging roads. Logging roads give colonists access to remote rainforest

areas.

Other causes of forest loss in the Amazon

Historically, hydroelectric projects have flooded

vast areas of Amazon rainforest. The Balbina dam flooded some 2,400

square kilometers (920 square miles) of rainforest when it was

completed. Today dams drive deforestation by powering industrial mining

and farming projects. Hundreds of dams are planned in the Amazon basin

over the next 20 years.

Mining has had a substantial impact in the Amazon.

High mineral and precious metal prices has spurred unprecedented

invasions of rainforest lands across Brazil, Venezuela, Colombia, French

Guiana, Suriname, Guyana, and Peru. A 2013 study found that the area

torn up for small-scale gold mining increased 400 percent in 13 years.

Oil and gas development is fueling environmental

concerns in the Western Amazon. Large blocks of rainforest have been

granted for exploration and exploitation licenses in recent years.

Deforestation monitoring in the Amazon rainforest

This section is excerpted for an story published on Mongabay News: What’s the current deforestation rate in the Amazon rainforest?

Nearly two-thirds of the Amazon rainforest is located

in Brazil, making it the biggest component in the region’s

deforestation rate. Helpfully, Brazil also has the best systems for

tracking deforestation, with the government and Imazon, a national civil

society organization, releasing updates on a quarterly and monthly

basis using MODIS satellite data, respectively. Both the Brazilian

government and Imazon release more accurate data on an annual basis

using higher resolution Landsat satellite imagery.

For other Amazon countries — primarily Colombia,

Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia since Venezuela, Suriname, Guyana and French

Guiana are mostly outside the true Amazon basin watershed — the most

reliable source for regular updates is Global Forest Watch, a platform

that aggregates data from a many different sources. Currently Global

Forest Watch has FORMA, a near-real-time forest cover monitoring system

that also uses MODIS, and annual estimate made by a group of researchers

led by a team at the University of Maryland.

Variance in monthly deforestation

Month-to-month deforestation is highly variable

leading to frequent misreporting in the media. Both MODIS and Landsat

cannot penetrate cloud cover, so during the rainy season — from roughly

November to April — estimates are notoriously unreliable when compared

to the same month a year earlier. Furthermore, most forest clearing in

the Amazon occurs when it is dry. So if the dry season is early,

deforestation may increase earlier than normal. For these reasons, the

most accurate deforestation comparisons are made year-on-year. For

Brazil, the deforestation “year” ends July 31: the peak of the dry

season when the largest extent of forest is typically visible via

satellite.

Nonetheless, short-term MODIS data isn’t useless — it

can provide insights on trends, especially over longer periods of time.

Generally, comparing 12 consecutive months of MODIS data will provide a

pretty good indication of deforestation relative to other years.

Therefore the charts below include a history of MODIS-based data as well

as the longer-term Landsat-based data. The MODIS system used by

Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE) is called DETER,

while Imazon’s system is called SAD. INPE’s annual Landsat-based system

is called PRODES.

Current monthly deforestation data for the Brazilian Amazon

INPE and DETER are used primary for law enforcement

since detection occurs on roughly a biweekly basis, enabling

environmental police to take action as large-scale forest clearing

occurs. The Brazilian government has cited “law enforcement” as the

reason it has switched to quarterly public releases of data, asserting

that more frequent releases could undermine the effectiveness of taking

action against illegal tree-felling.

Comments

Post a Comment

Feel Free and open to share your thoughts